On May 18th, the inaugural flight of Air Asia’s new route, Kuala Lumpur, Hua Hin & back, flew in to Hua Hin with much fanfare. Disembarking guests were greeted by Thai dancers, the Mayor of Hua Hin and a terminal full of dignitaries.

On May 18th, the inaugural flight of Air Asia’s new route, Kuala Lumpur, Hua Hin & back, flew in to Hua Hin with much fanfare. Disembarking guests were greeted by Thai dancers, the Mayor of Hua Hin and a terminal full of dignitaries.

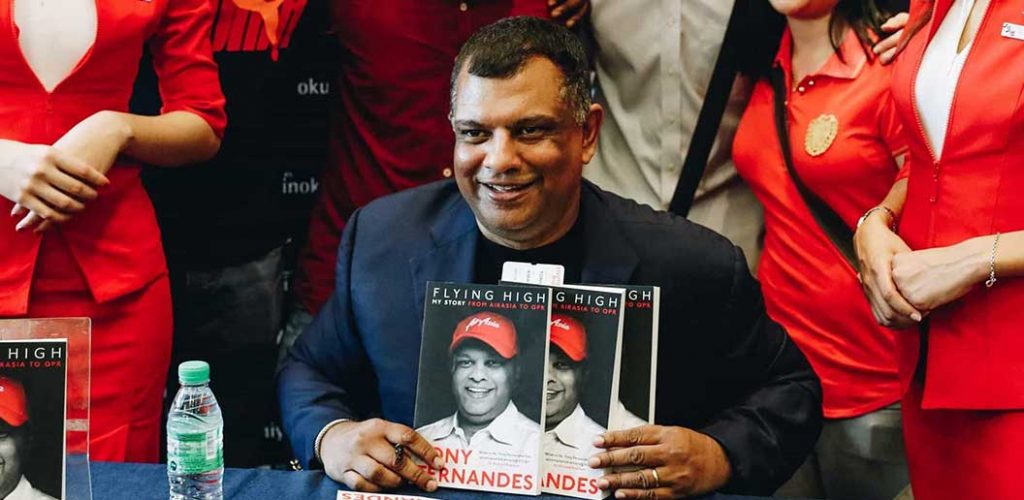

An interesting story, but, an even greater story is that of Anthony “Tony” Fernandes. Tony is the founder of Air Asia and is one of the best-known airline chiefs in the world. He’s revered for taking Asia’s first low-cost airline up from near-bankruptcy to a company with more than 7,000 employees and a $2 billion valuation. For nine years in a row, AirAsia has won awards for being the world’s best no-frills airline by Skytrax Awards, dubbed the “Oscars” of the Aviation Industry. The Airline operates scheduled domestic and international flights to more than 165 destinations spanning 25 countries.

In 2001, Fernandes was a music industry magnate for Warner Music with no airline experience. One evening he was sitting in a bar and happened to notice a television interview with Stelios Haji-Ioannou, the billionaire founder of the wildly successful, no-frills carrier EasyJet. He was riveted. “I [just] loved airports,” Fernandes says. “I thought they were happy places, and I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool to own an airline? ”

In 2001, Fernandes was a music industry magnate for Warner Music with no airline experience. One evening he was sitting in a bar and happened to notice a television interview with Stelios Haji-Ioannou, the billionaire founder of the wildly successful, no-frills carrier EasyJet. He was riveted. “I [just] loved airports,” Fernandes says. “I thought they were happy places, and I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool to own an airline? ”

Fernandes decided he, too, could build a low-budget airline.

Advisors told Fernandes to buy an existing airline rather than develop one from scratch, and soon a little-known airline called AirAsia caught his eye. Owned by the Malaysian government, it had just two aircraft, a staff of 250 and debts of more than $11 million. Along with that debt burden was a guarantee that the airline’s parent company, DRB-Hicom, had made to GE Capital Aviation Services (GECAS), potentially blocking a deal.

In order to close the deal, Fernandes needed GECAS to drop the guarantee. He decided to cold call Mike Jones, a director at GECAS in Singapore, and the two met at the airport to chat over a cup of coffee. “Take a risk on me,” the entrepreneur told him.

The risks were obvious. Fernandes was not only an unknown quantity, but conventional wisdom at the time also suggested no-frills airlines wouldn’t work in Asia like they did in Europe and the United States. Flying at the time was considered something only for the affluent, and it was unclear whether average consumers would purchase low-cost tickets.

The risks were obvious. Fernandes was not only an unknown quantity, but conventional wisdom at the time also suggested no-frills airlines wouldn’t work in Asia like they did in Europe and the United States. Flying at the time was considered something only for the affluent, and it was unclear whether average consumers would purchase low-cost tickets.

Yet to Jones, Fernandes displayed the boldness necessary for a business that deals with breathtakingly high numbers. (A decade later, Fernandes would make one of the largest-ever single orders for commercial aircraft in history, buying 200 aircraft from Airbus with a list value of $18 billion.) “He had a very strong vision for what he wanted the airline to be,” Jones says. “He had a huge amount of energy.”

After more meetings with GECAS managers in the U.S., GECAS agreed to drop its guarantee, allowing the former music executive to buy AirAsia for the token sum of one ringgit (about US$0.26 at the time) with US$11 million worth of debts. Fernandes turned the company around, producing a profit in 2002 and launching new routes from its hub in Kuala Lumpur, undercutting former monopoly operator Malaysia Airlines with promotional fares as low as 1 ringgit. In 2003, AirAsia launched its first international flight to Bangkok. Fernandes mortgaged his home and used all his savings to help start to pay off the company’s debt. He then went to GECAS again to help him lease a handful of secondhand aircraft to grow AirAsia’s fleet. “That was the making of AirAsia,” Fernandes says.

After more meetings with GECAS managers in the U.S., GECAS agreed to drop its guarantee, allowing the former music executive to buy AirAsia for the token sum of one ringgit (about US$0.26 at the time) with US$11 million worth of debts. Fernandes turned the company around, producing a profit in 2002 and launching new routes from its hub in Kuala Lumpur, undercutting former monopoly operator Malaysia Airlines with promotional fares as low as 1 ringgit. In 2003, AirAsia launched its first international flight to Bangkok. Fernandes mortgaged his home and used all his savings to help start to pay off the company’s debt. He then went to GECAS again to help him lease a handful of secondhand aircraft to grow AirAsia’s fleet. “That was the making of AirAsia,” Fernandes says.

Few people know that airlines don’t own many of the airplanes they fly. In fact, they lease around 40 percent of their fleets on average today. The number of leased planes was less than 1 percent some 50 years ago. The trend has taken off because it leaves airlines with extra capital to operate the business, and it spreads more risk to the lessor. The model is a bit like leasing a car — especially as technologies change, an airline might want the option to upgrade some of its aircraft sooner than a plane’s typical 25-year-lifespan.

Few people know that airlines don’t own many of the airplanes they fly. In fact, they lease around 40 percent of their fleets on average today. The number of leased planes was less than 1 percent some 50 years ago. The trend has taken off because it leaves airlines with extra capital to operate the business, and it spreads more risk to the lessor. The model is a bit like leasing a car — especially as technologies change, an airline might want the option to upgrade some of its aircraft sooner than a plane’s typical 25-year-lifespan.

It certainly worked for Fernandes. Within a year of buying AirAsia and subsequently growing his fleet, he’d cleared all the company’s debts thanks partially to a growing traveling class in Asia. In 2016, an estimated 100 million Asians took their first plane ride. And while Fernandes now has the capital to buy jets directly from Airbus, he chose to sit down with Jones and the GECAS team in late 2016 to discuss leasing some airplanes again.

That initial meeting over coffee was not only a catalyst to building one of the world’s most successful airlines, it provided an important lesson for Fernandes too. “In my whole life, any email that comes to me I always take it very seriously,” he says. “I learned a little bit of that from Mike Jones because he didn’t fob me off. You never know what can come from it.”

Fernandes was born in 1964 in Kuala Lumpur. The seeds of his entrepreneurialism were sown early on. “One of my business heroes would have to be my mom,” he explains. “She brought Tupperware to Malaysia, and I grew up watching her sell the containers and hold Tupperware parties. She could sell ice to an Eskimo.”

He was educated in the UK, graduating from the London School of Economics in 1987. Soon after that, he got his first taste of the blend of accountancy and dynamic business, working at Virgin Atlantic as an auditor, then becoming financial controller for Richard Branson’s Virgin Records from 1987 to 1989.

But his interest in general management, and his ambition, was already evident. Back in Malaysia – and still comfortably in his twenties – he became MD of the local Warner Music Group business, rising to South East Asian regional vice president by 1992.

That all ended when Time Warner merged with AOL in 2001. And it left the still-young Fernandes with the burning question: what next?

“I’d wanted to own an airline for a long time,” he says. “At 12 years old, I was sent to boarding school in the UK, which was terribly far away from my family in Malaysia. I was always longing to visit home, but every time I called my parents, they told me it was too expensive. So I dreamt of someday owning an airline so I could fly whenever I wanted to.”

Fernandes already knew it was possible to rip up the rulebook in well-established industries and create something that really served customers’ needs. When low-cost airlines began to make a dent on the incumbent carriers – companies like SouthWest in the US and EasyJet and RyanAir in Europe – it became clear that there was a real opportunity to realise his boyhood dream.

Fernandes already knew it was possible to rip up the rulebook in well-established industries and create something that really served customers’ needs. When low-cost airlines began to make a dent on the incumbent carriers – companies like SouthWest in the US and EasyJet and RyanAir in Europe – it became clear that there was a real opportunity to realise his boyhood dream.

Tony’s advice for entrepreneurs looking to ride the wave is simple: “Believe the unbelievable, dream the impossible, never take no for an answer,” he concludes. “It doesn’t matter what your job is, just believe in yourself and go for your dreams.”