Hans Eberhard Wilhelm Wilsdorf was born in Kulmbach, Bavaria, Germany on March 22, 1881. Wilsdorf was the son of a hardware store owner. His mother was a descendent of the Maisel Bavarian brewing dynasty. At the age of 12, Hans lost both his parents, dying within months of each other.

Hans and his siblings were left in the care of his aunt and uncle. They sold the family hardware business and placed the proceeds into the Wilsdorf Trust until the heirs reached of age. Although the Wilsdorf Trust started as a result of tragedy, it was the basis for the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation initiated later in Wilsdorf’s life.

Hans went to boarding school in Coburg Germany, excelling in math and languages, particularly English. After boarding school, at the age of 18, Hans secured a position at a pearl distribution company gaining knowledge of world trade and the jewelry industry. He also developed a fascination of technology.

When Hans turned 20, he went to work for the watch exporting firm of Cuno Korten in the Swiss City of La Chaux-de-Fonds. There, he was exposed to pocket watches and timepiece technology and worked with the company’s English clients.

In 1903, at the age of 22, he decided to move to London to set up residence and gain British citizenship. During his travel, thieves stole his inheritance which totaled 33,000 German gold marks. Undeterred, Hans continued to work in the watch industry and decided that he wanted to start his own watch company.

At the age of 24 Hans had a fateful meeting with Alfred James Davis and together they partnered to build their own watch making company. Davis had the money to invest and Hans had the watchmaking knowledge from his experiences at Cuno Korten. The partnership was further strengthened when Davis married Wilsdorf’s younger sister.

Wilsdorf utilized money borrowed from his siblings to match Davis’ investment. As a result, they each owned 50% of the company. As equal partners, they complimented each other’s skills and backgrounds. Hans knew watches and Davis knew financing and international trade. They started Wilsdorf & Davis Ltd, incorporating watch movements from the company Jean Aegler, a firm he learned of while working at Cuno Korten. Keeping focused, Wilsdorf & Davis only produced two watches, the pocket watch and a purse watch, respectively for men and women.

In the early 1900’s, wristwatches were called “wristlets” and were small in size, small in number, not very accurate, and worn primarily by women. Gentlemen were quoted to say they “would sooner wear a skirt as wear a wristlet.”

However, Wilsdorf cleverly noted that during the Boer War, the heat prevented soldiers from wearing jackets, and, during battle, it was incredibly inconvenient to fumble around for a pocket watch. As a result, soldiers found themselves strapping small pocket watches on their wrists. This inspired Wilsdorf to specialize in what was then a non-existent market.

In 1908, Wilsdorf returned to Bienne and negotiated with Aegler for a consistent supply of watch movements. It was the largest contract ever signed for the watch component at the time. Concurrently, trademark and logo styles were an industry trend. The name Wilsdorf & Davis did not have the same sound as Kodak and Coke. Wilsdorf & Davis set upon thinking of a company name that doesn’t mean anything in particular, is easy to pronounce in multiple languages, is hard to misspell, and decided on a name.

…That name was Rolex.

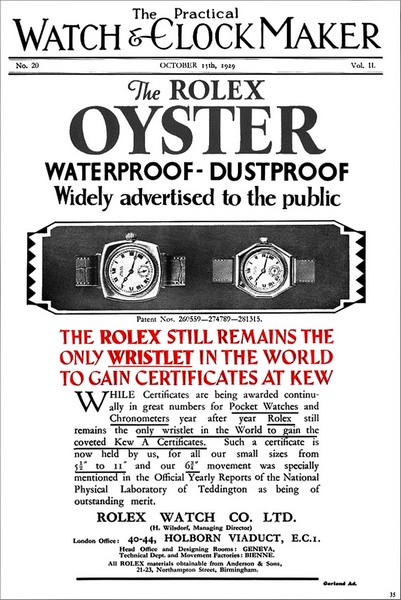

Dispelling the myth that wristwatches are not accurate, Rolex sent its first movement to the School of Horology in Bienne in 1910, one of the early timekeeping institutes where Rolex was awarded the world’s first wristwatch chronometer rating. With the rating, Rolex overcame the first challenge to keep accurate time. Further proving the accuracy of well-built wristwatch movements, Rolex was awarded the “Class A Certificate of Precision” from the Kew Observatory in England, the first certificate awarded to a wristwatch.

The test involved 45 days in five positions and three temperatures. Prior to Rolex, these certificates were only awarded to marine chronometers. Realizing the value of timing certificates, Wilsdorf insisted that all Rolex timepieces undergo similar testing and no Rolex should be sold without its “Official Timing Certificate.” For Aegler, Rolex would not accept any movements unless they passed Rolex’s seven-day battery of tests. Accepting no less than a timing certificate, Rolex set the timing standard for the rest of the watch industry.

The company was on sure footing with a consistent supply of watch movements from Aegler, a registered brand name, and a product that was in high demand. The start of World War I further helped wristwatch demand but brought anti-German trade restrictions to England. Because of the high tariffs on watch and jewelry components coming into England, Wilsdorf and Davis decided to move much of the production back to Bienne utilizing the partnership they forged with Hermann Aegler.

In 1919, Rolex purchased a percentage of the Aegler company and began to call itself Aegler S.A. Rolex Watch Company. Soon after that, Wilsdorf bought out Davis’s share of the company and moved the office to Geneva where he registered “Montres Rolex S.A.” on January 17th. Wilsdorf settled in Geneva in order to let the factory in Biel be entirely devoted to manufacturing watch movements where Geneva would focus upon creating case models that fit cosmopolitan tastes.

On May 2, 1925, Rolex trademarked the famous crown or coronet in Geneva, Switzerland. After an expensive advertising campaign in 1926 to raise brand awareness, the “Rolex” name started appearing on every dial and the Rolex name quickly became synonymous with quality and distinction.

Another production benchmark in 1925 happened when Rolex addressed the weak spot in all watch cases, the winding stem and its predilection for leaking water and dust. Wilsdorf heard of a patent filed for a new winding stem and button/crown. Wilsdorf bought the patent and registered the world’s first waterproof case, the Oyster, on July 29, 1926 in Switzerland, and again in London on February 28, 1927.

The term Oyster came to Hans while trying to open an oyster at a dinner party. Opening Rolexes today requires special tools, very similar to opening an Oyster at a restaurant. The sealed crown, combined with a water tight synthetic crystal also introduced at the time, along with a threaded bezel and caseback, Hans now had the three main watch deficiencies addressed, the crown, the case, and the timing accuracy.

1931 brought disaster and opportunity. Rolex business flourished, but the British pound was drastically devalued on September 21 as a result of the world economic crisis and the Great Depression. The devaluation caused Rolex prices to rise, decreasing exports by 60%. If Rolex were to survive, it would have to sell outside of the British Empire.

Subsequently, Wilsdorf established subsidiaries in Paris, Buenos Aires, and Milan as well as exploring business activities in the Far East. The expansion was successful. Rolex increased production of Rolex Oysters from 2,500 to approximately 30,000 watches a year.

In 1944, Wilsdorf’s wife May died in addition to his long-time business partner and friend Hermann Aegler. This left Wilsdorf as Rolex’s sole owner. With no heirs, Wilsdorf created the Hans Wilsdorf foundation in 1945. The trust was underwritten to provide strict direction on how the company was to be run after Wilsdorf’s death, ensuring that the company would never merge with another company, be sold, or publicly traded.

In 1945, Rolex introduced the date window to mark the firms 40th birthday. The DateJust caliber 740 was the world’s first automatic date mechanism in a wristwatch. Called the DateJust because, well, Date is obvious, but “Just” stands for “just in time,” advancing precisely at midnight without delay. The date window was located on the right edge at 3:00 o’clock because most wearers have their watch on their left arm and the date window can easily peak out from under a shirt sleeve.

The Rolex Sir Edmund Hillary wore to the peak of Mount Everest

The 1950’s were a decade of post war growth and achievement for Rolex. On May 29, 1953, the experimental Rolex Explorer rose to 29,035 ft above sea level on the wrist of Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay. In the same year, they attached a specially designed Deep Sea Special to the exterior of Auguste Piccard’s bathyscaphe, which reached a depth of 10,335 ft. This proved the concept that watches can be as pressure proof as submarines.

Closing out the decade in 1959 was the introduction of the Submariner 5512, water resistant to 200 meters along with the introduction of crown guards that are prevalent on all Rolex sport watches. Also during the early 1950’s, Rolex incorporated the venerable Cyclops window to the date aperture after Wilsdorf’s near-sighted second wife could not read the date on her watch. Also, during the 1950’s Rolex had planted subsidiaries in Bombay, Brussels, Buenos Aires, Dublin, Havana, Johannesburg, London, Milan, Mexico City, New York, Paris, Sao Paulo and Toronto.

The Final Tick. 1960 saw the passing of Rolex’s founder Hans Wilsdorf on July 6th leaving Rolex to appointees stated in the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation.

For over a century, Rolex watches have accompanied explorers and achievers around the world, from the top of the highest mountains to the deepest reaches of the ocean. You’ll find Rolex present at the most prestigious events in golf, sailing, tennis, motor sport, and equestrian tournaments. Synonymous with power and success, some of history’s most colourful personalities, from Winston Churchill to Cuban leader Fidel Castro, have worn Rolex watches.

If it would be possible to communicate thru dimensions, it would be interesting to ask Hans Wilsdorf if he knew back when he started, that his Rolex “wristlets” would make such a unique and lasting contribution to global culture, science and exploration.